Hisako

Hibi

“Art consoles the spirit, and it continues on in timeless time”

– Hisako Hibi

Hisako Shimizu Hibi (1907-1991) was an Issei (first-generation) artist whose work is deeply rooted in and inspired by the San Francisco Bay Area. When she was a teenager, her Japanese family immigrated to the U.S. and settled in California, where she later studied at the California School of Fine Arts and exhibited her work at the San Francisco Art Association. She married her fellow student Matsusaburo Hibi, with whom she moved to Mt. Eden and Hayward. There, they raised their two children, Satoshi and Ibuki, until the family was forced into internment camps in 1942. The publication of her memoir, Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, was accompanied by an exhibition of sixty-three oil paintings at the Japanese American National Museum.

“The house was a happy one with my husband and our two children, Satoshi “Tommy” and Ibuki “Peek-a-boo.” We lived in a little town near San Francisco, and our home had an apricot orchard on one side and a wide stretch of tomato fields on the other. […] The plants grew well here – our new land.”

The Hibis created a colorful, lively, and happy home by embracing American culture while maintaining their Japanese identity. In Hayward, they found a place to build a home and express themselves culturally and creatively. The garden had a special meaning for them as this was where they grew vegetables and planted many trees, including an apricot orchard that became a central motif of Hibi’s paintings.

Hisako Hibi

“Art consoles the spirit, and it continues on in timeless time”

– Hisako Hibi

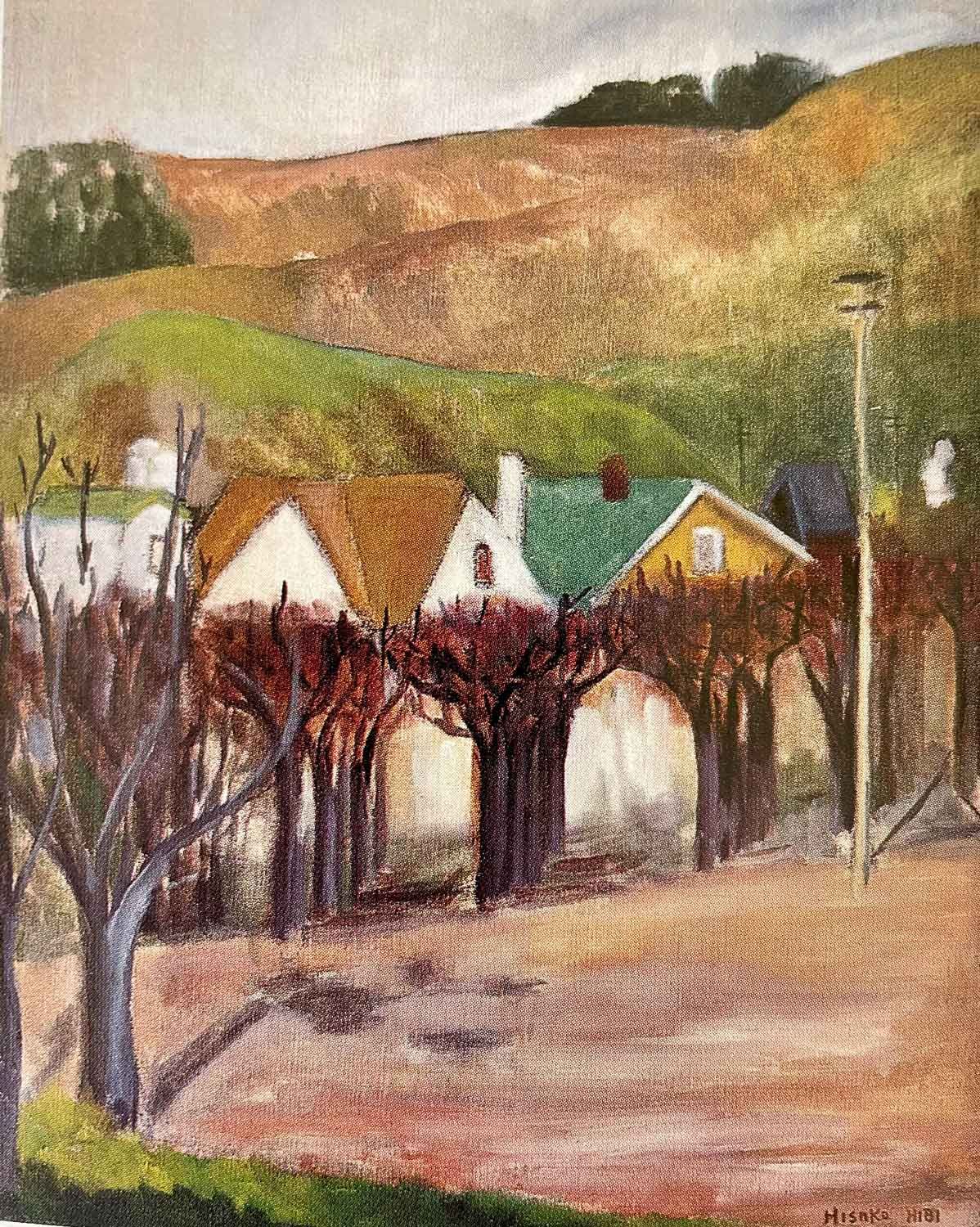

Apricot Trees Along Jackson Street

Apricot Trees Along Jackson Street

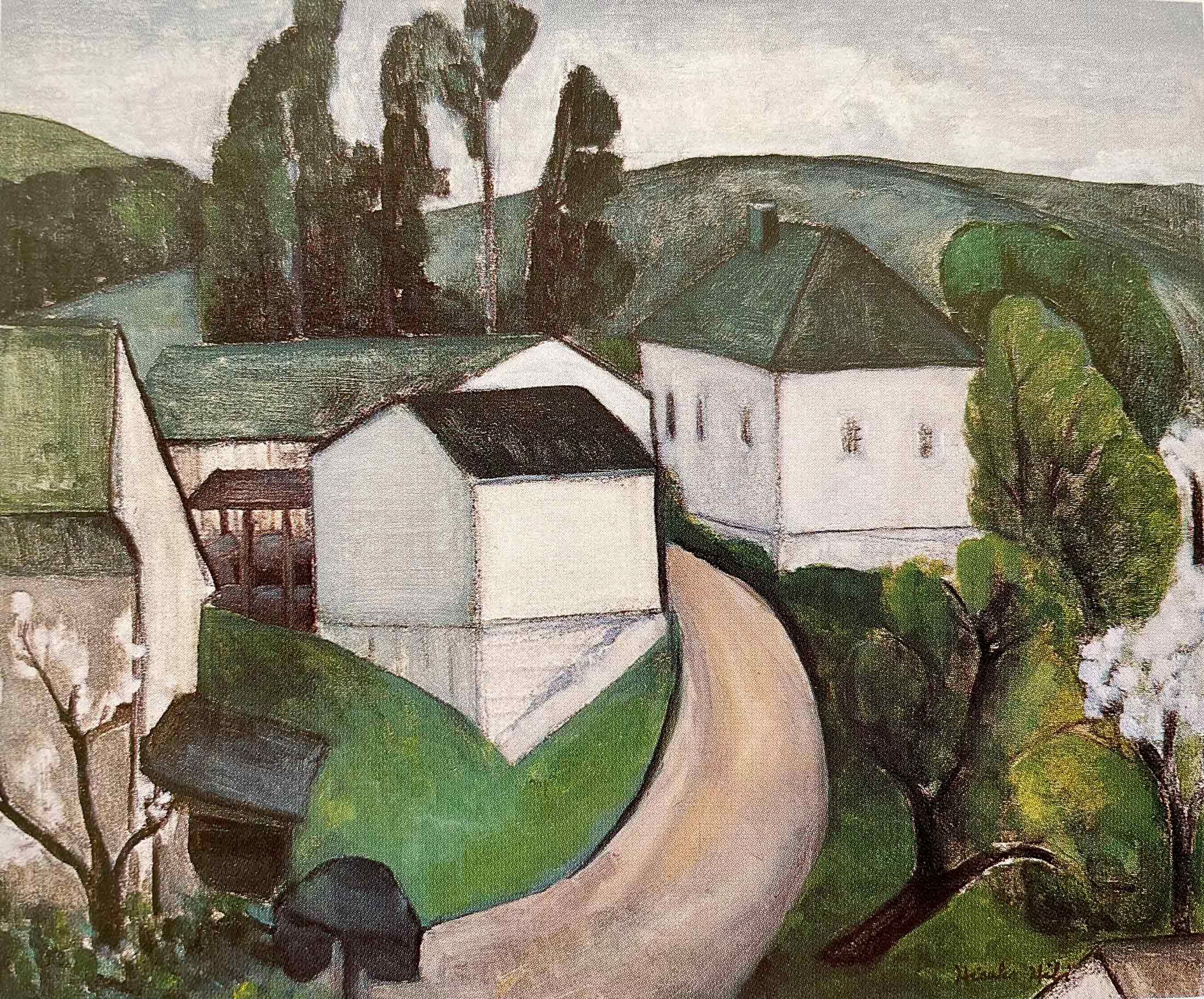

Spring #2

Spring #2

Even with the threat of imminent internment, Hisako Hibi and her family did not stop caring for their home. This fact testifies to her closeness to nature and rootedness in Hayward, which are reflected in her art. This painting, depicts Hayward in lighter, less vibrant colors. It depicts a man in a straw hat cultivating a field surrounded by chickens and blooming trees at the foot of a hill. In the distance, birds pass over vast fields and lonesome houses.

Even with the threat of imminent internment, Hisako Hibi and her family did not stop caring for their home. This fact testifies to her closeness to nature and rootedness in Hayward, which are reflected in her art. This painting, depicts Hayward in lighter, less vibrant colors. It depicts a man in a straw hat cultivating a field surrounded by chickens and blooming trees at the foot of a hill. In the distance, birds pass over vast fields and lonesome houses.

Internment

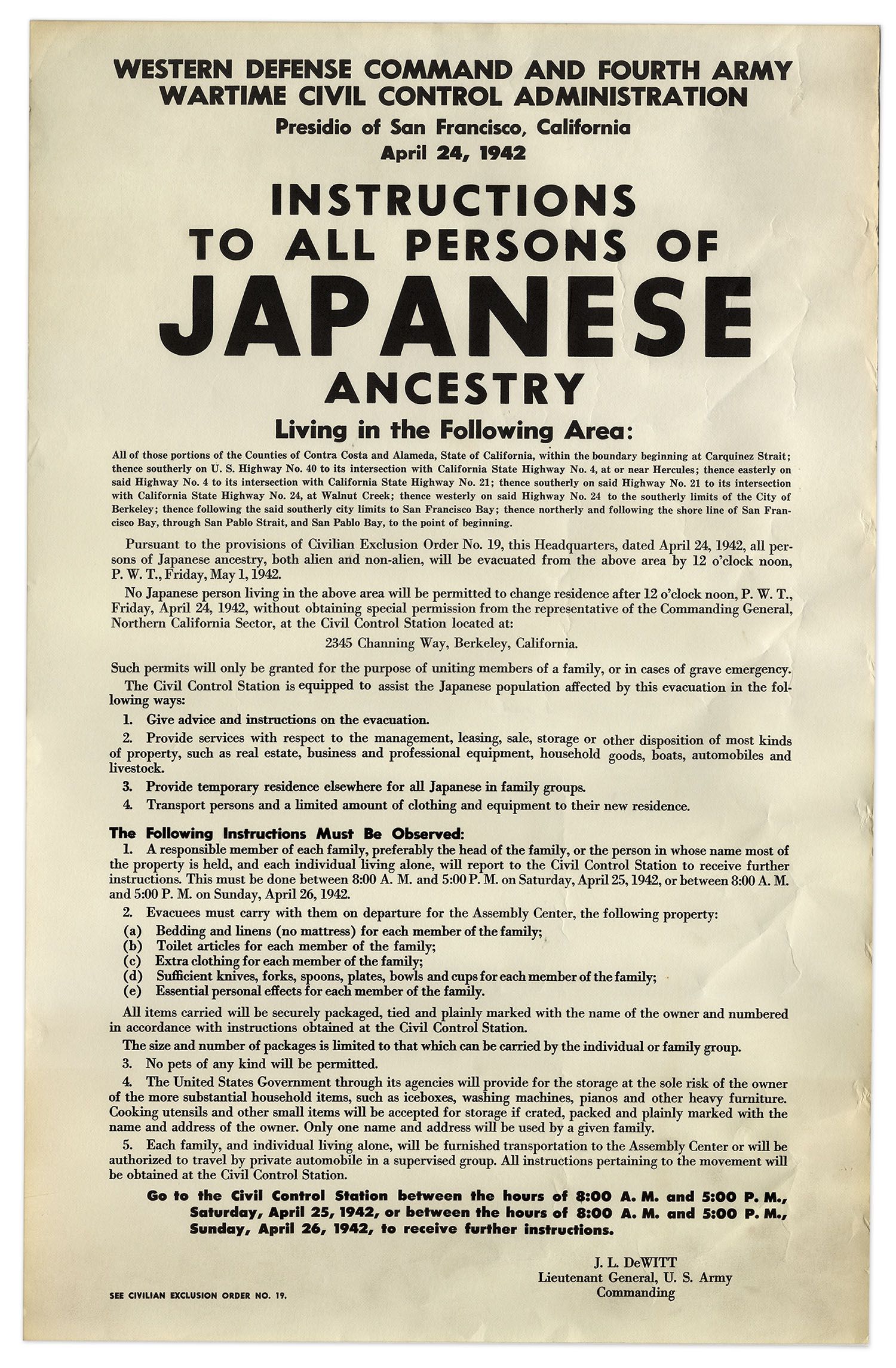

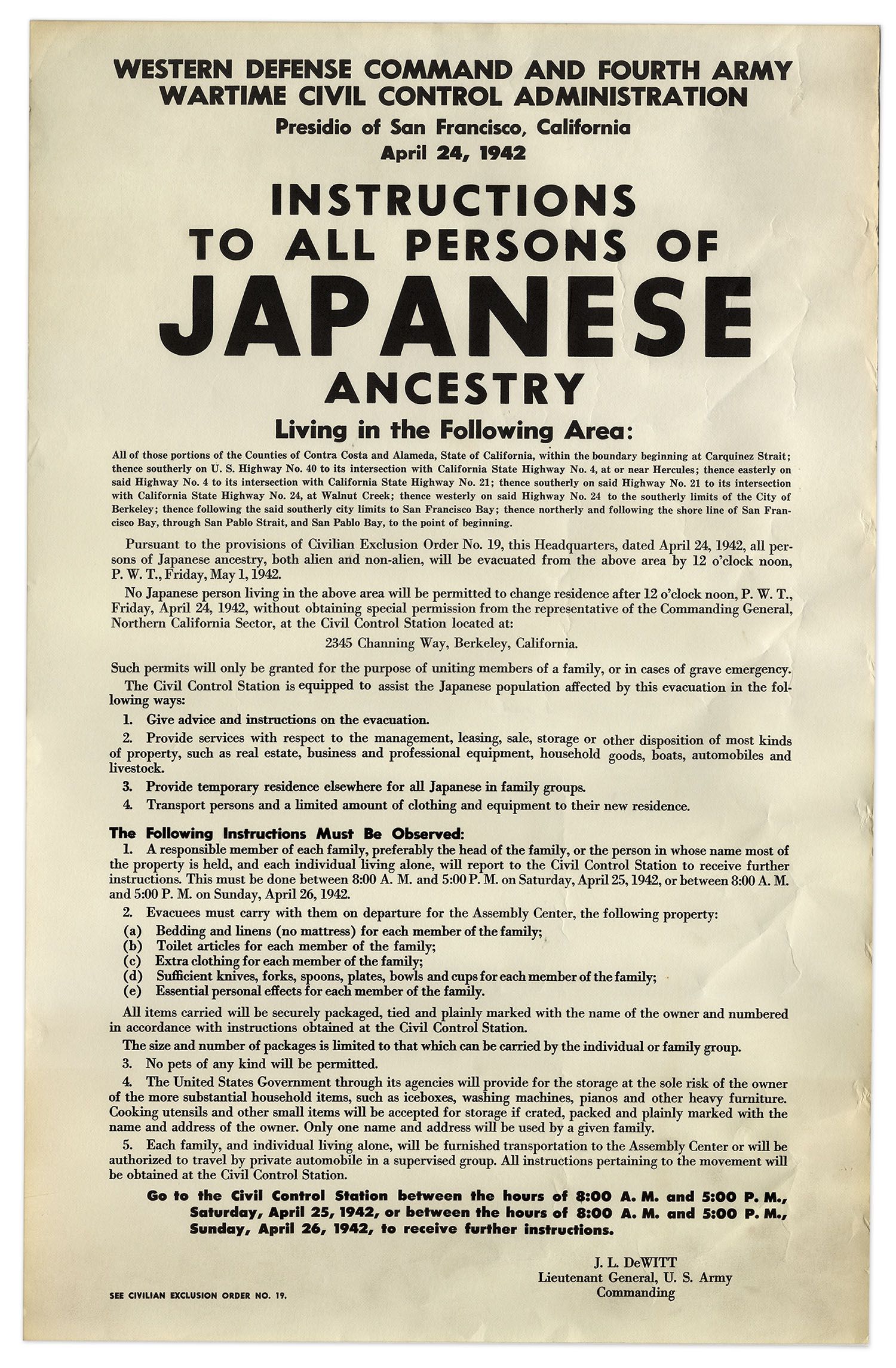

Image: Nate D. Sanders Auctions. Lot#261 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster. Lot Detail – 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster — For Japanese Residents of San Francisco (natedsanders.com)

With the prospect of eventually returning, the Hibi family distributed a portion of their paintings to local hospitals, schools, clubs, and libraries before their internment. This act of sharing enabled the Hibi’s to safeguard a portion of their art while showing their appreciation of the Bay Area and the friendships they had made. Although the Hibi’s would soon be gone, a part of them would remain here in Hayward.

Internment

With the prospect of eventually returning, the Hibi family distributed a portion of their paintings to local hospitals, schools, clubs, and libraries before their internment. This act of sharing enabled the Hibi’s to safeguard a portion of their art while showing their appreciation of the Bay Area and the friendships they had made. Although the Hibi’s would soon be gone, a part of them would remain here in Hayward.

Image: Nate D. Sanders Auctions. Lot#261 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster.

Lot Detail – 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster — For Japanese Residents of San Francisco (natedsanders.com)

Image: Dorothea Lange, “Hisako and Ibuki Hibi with doll awaiting the bus to Tanforan,” Photograph, May 9, 1942, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 13, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

“May 8, 1942, evacuation day, was a beautiful spring day. Matsusaburo was up early and watered the vegetable garden, flowers, and trees around the house we rented for ten dollars per month. The hummingbirds were hovering over the honeysuckle vines around the front porch. The dark pink peach tree was in full bloom because it was the time of Tango-no-sekku, Boys’ Day. The new bamboo shoots were pointing straight up toward the sun. With its tender, new leaves and sparrows on its branches, the old oak tree seemed to be at peace, saying goodbye to the family.”

“The man, a stranger, priced the items of furniture himself. He gave me twenty-five dollars for the piano, five dollars for a living room rug, and so on. Helplessly, the family watched the truck speed away.”

Due to the uncertainty of not knowing if or when the Japanese Americans would return, individuals sold most of their possessions before their departure, often at bargain prices. When the day of evacuation came, men, women, and children could only take what they could carry, including bedding and linens, toiletries, clothing, cooking utensils, and essential personal effects.

Image: Dorothea Lange, “Hisako and Ibuki Hibi with doll awaiting the bus to Tanforan,” Photograph, May 9, 1942, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 13, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

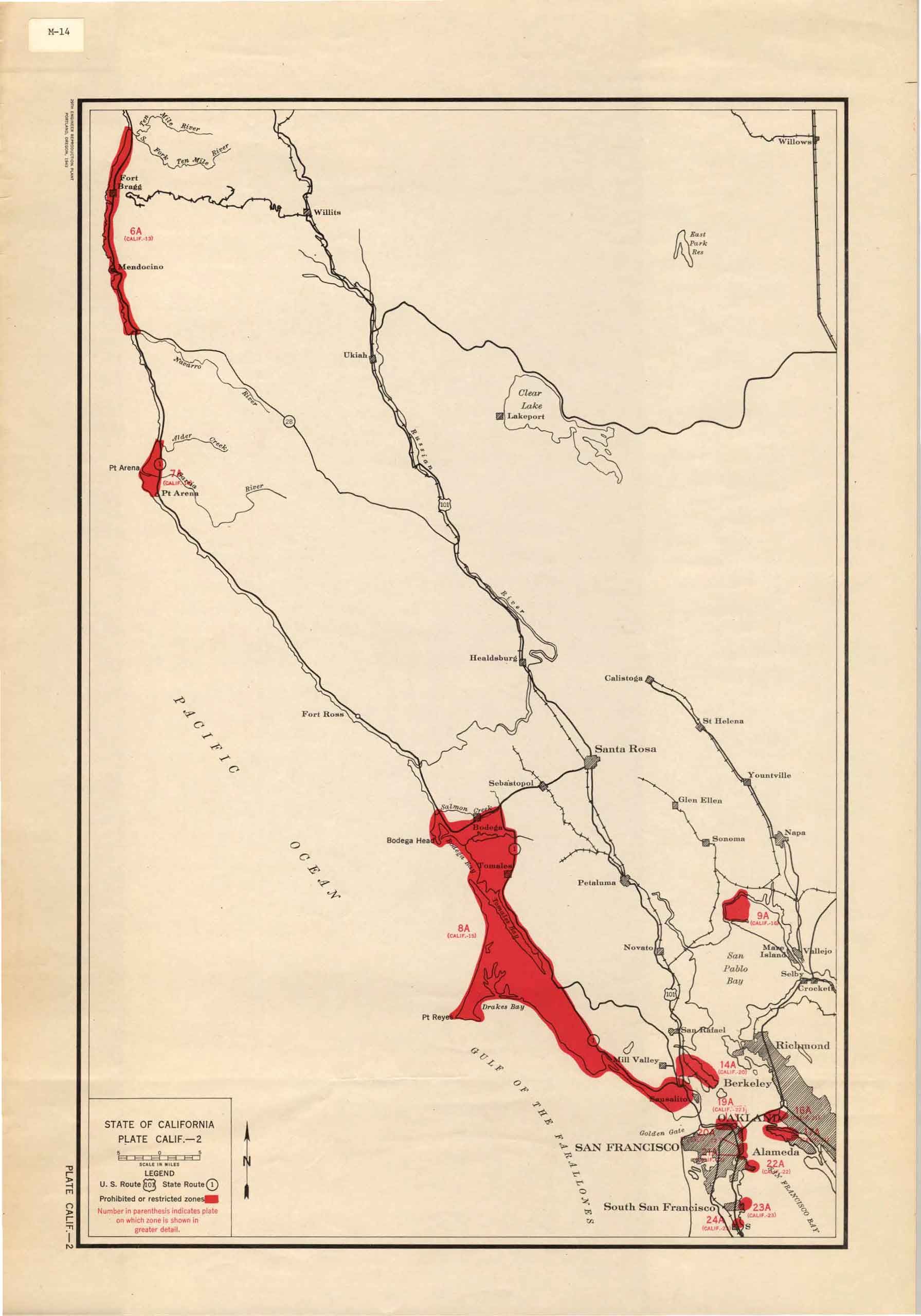

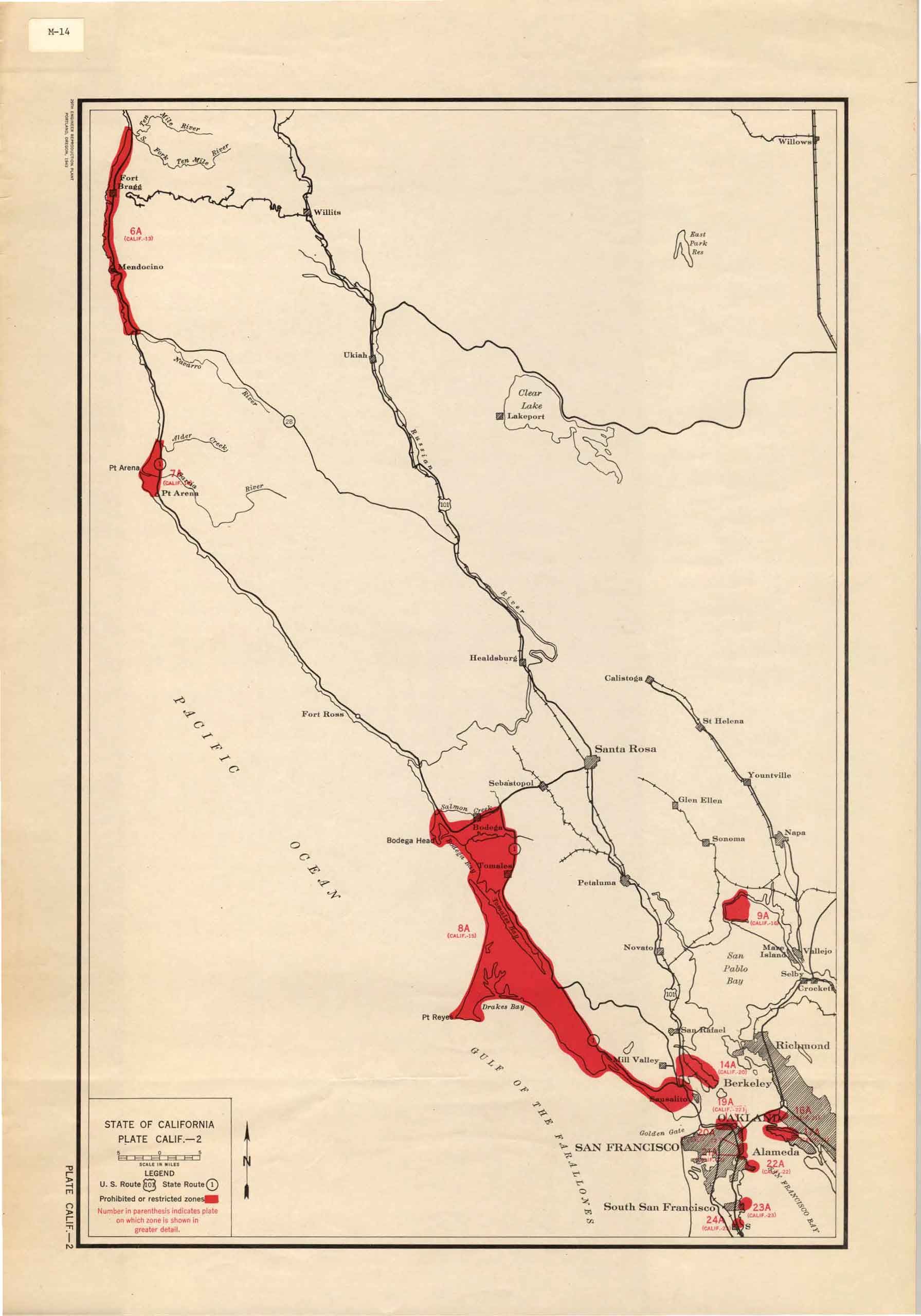

The map shows restriction zones for Japanese Americans in the Northern California coast area from San Francisco to Fort Bragg (including parts of Fort Bragg, Mendocino, the Botega Bay region, San Francisco, and Oakland).

The map shows restriction zones for Japanese Americans in the Northern California coast area from San Francisco to Fort Bragg (including parts of Fort Bragg, Mendocino, the Botega Bay region, San Francisco, and Oakland).

“Although unbelievable today, it did happen in San Francisco, in Oakland, in towns near the beaches, in the villages between the valleys, and all along the Pacific Coast from the state of Washington down to California and to parts of Arizona in 1942. Japanese were uprooted from their homes. Yesterday’s friends were today’s enemies. The air of alienation and hostility was felt everywhere.”

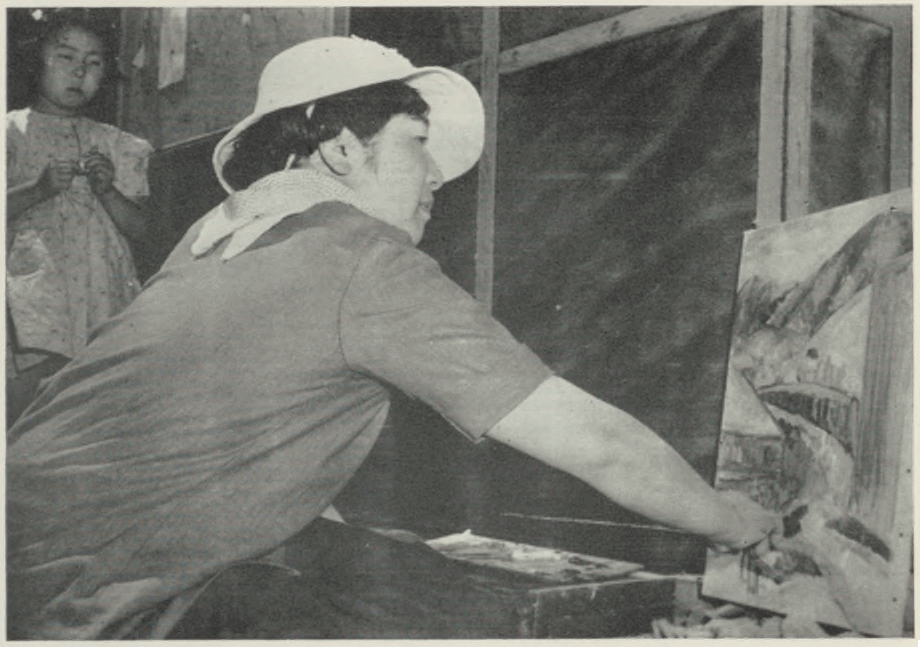

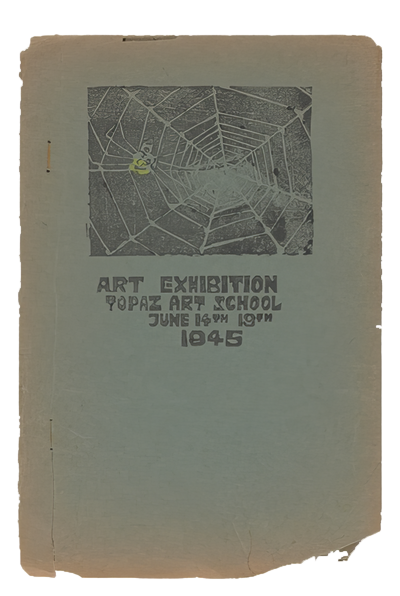

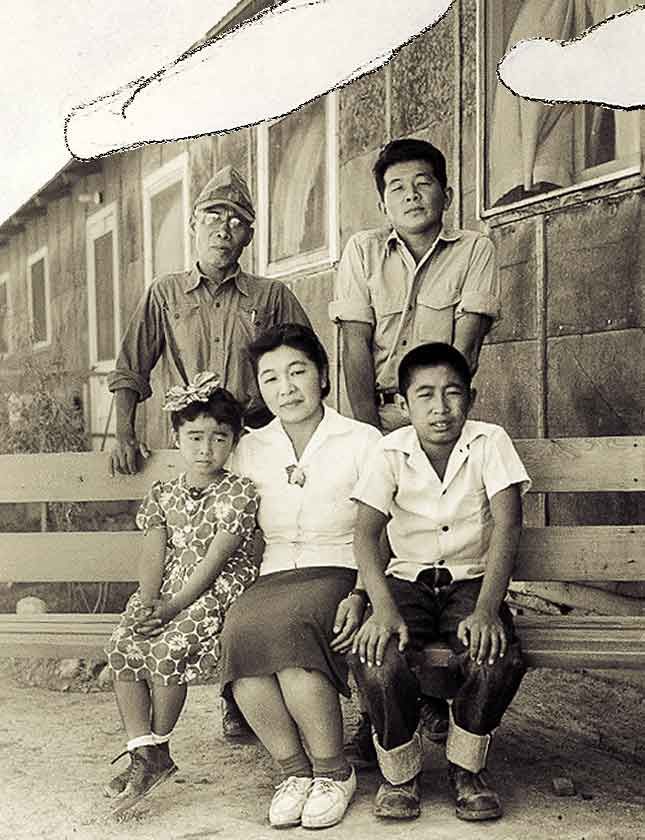

During the Hibi’s incarceration at Tanforan and Topaz, they helped organize and operate an art school for all ages with the assistance of other Japanese artists and prisoners. Although incarcerated, art exhibitions were held displaying various types of artwork. The Hibis’ contributed their pieces alongside their students.

Matsusaburo Hibi recited traditional philosophy to his children to give them courage as they were transferred between incarceration camps, Tanforan Detention Center in San Bruno, California, and Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. Men, women, and children alike were housed in barracks, some still under construction, often without a roof and lacking mattresses or other basic facilities. These prisoners were cut off from the outside world.

Upon the Hibi family’s release from Topaz in 1945, they moved to New York City, hoping for a new start. Unfortunately, Matsusaburo passed from cancer within two years of their release, leaving Hisako and her children to carry on without him.

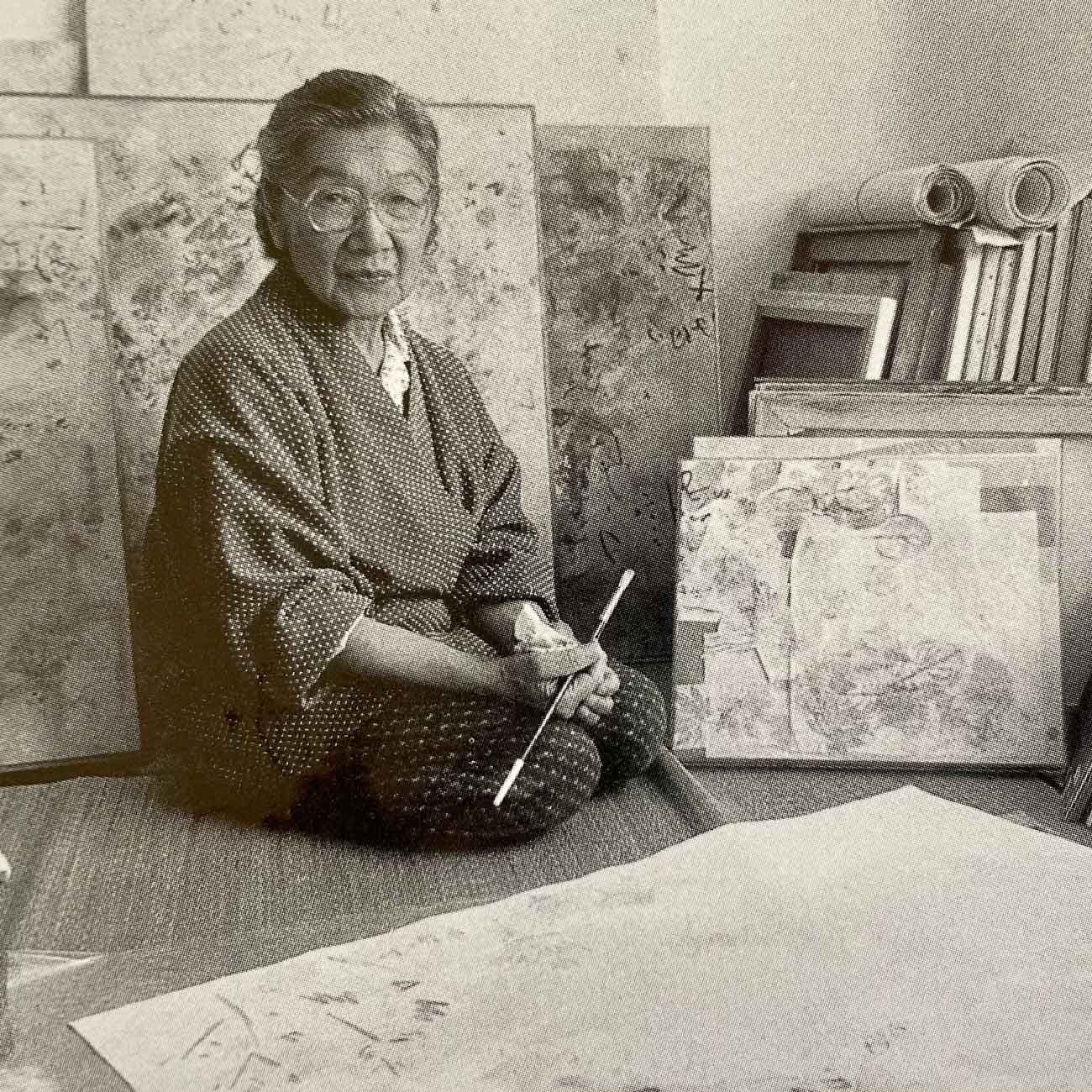

During the mid-1950s, after earning her U.S. citizenship, the family returned to the Bay Area. They settled in San Francisco, where Hisako grew as an artist and produced pieces displayed in museums and art galleries. Although Hisako did not re-establish her roots in Hayward, the city remained a place she would always consider home, where her family was once whole and happy.

Matsusaburo Hibi recited traditional philosophy to his children to give them courage as they were transferred between incarceration camps, Tanforan Detention Center in San Bruno, California, and Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. Men, women, and children alike were housed in barracks, some still under construction, often without a roof and lacking mattresses or other basic facilities. These prisoners were cut off from the outside world.

Upon the Hibi family’s release from Topaz in 1945, they moved to New York City, hoping for a new start. Unfortunately, Matsusaburo passed from cancer within two years of their release, leaving Hisako and her children to carry on without him.

During the mid-1950s, after earning her U.S. citizenship, the family returned to the Bay Area. They settled in San Francisco, where Hisako grew as an artist and produced pieces displayed in museums and art galleries. Although Hisako did not re-establish her roots in Hayward, the city remained a place she would always consider home, where her family was once whole and happy.

Four Seasons

Four Seasons is a metaphor for transition, change, loss, renewal, and the Hibi family’s journey. Upon the Hibi family’s release from Topaz in 1945, they moved to New York City, hoping for a new start. Unfortunately, Matsusaburo passed from cancer within two years of their release, leaving Hisako and her children to carry on without him.

During the mid-1950s, after earning her U.S. citizenship, the family returned to the Bay Area. They settled in San Francisco, where Hisako grew as an artist and produced pieces displayed in museums and art galleries. Although Hisako did not re-establish her roots in Hayward, the city remained a place she would always consider home, where her family was once whole and happy.

Four Seasons

Four Seasons is a metaphor for transition, change, loss, renewal, and the Hibi family’s journey. Upon the Hibi family’s release from Topaz in 1945, they moved to New York City, hoping for a new start. Unfortunately, Matsusaburo passed from cancer within two years of their release, leaving Hisako and her children to carry on without him.

During the mid-1950s, after earning her U.S. citizenship, the family returned to the Bay Area. They settled in San Francisco, where Hisako grew as an artist and produced pieces displayed in museums and art galleries. Although Hisako did not re-establish her roots in Hayward, the city remained a place she would always consider home, where her family was once whole and happy.

“Now I felt reborn in the natural beauty of the Bay Area, where I had gone to school and married. I have two children and five grandchildren. Time heals wounds.”

Additional Resources

For additional information regarding the lives and artwork of Hisako and “George” Matsusaburo Hibi, click the links below.

Citation – DeWitt, John L. Final Report – Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast. Photographic Figure 122, circa 1942. Published 1943, pp. 495. United States Army, Western Defense Command, 4th Division. Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing. Accessed February 17, 2024, from Final report, Japanese evacuation from the West Coast, 1942 – Digital Collections – National Library of Medicine (nih.gov)

Citation – Hibi, Hisako. Barrack 9, Apt. 6, San Bruno, CA. Oil on canvas. 1942. Japanese American National Museum. Accessed on February 17, 2024, from Barrack 9, Apt. 6, San Bruno, CA – Works – Hisako Hibi Collection – Featured Collections – Japanese American National Museum (emuseum.com)

Citation – Hibi, Hisako. Floating Clouds. Oil on canvas. 1944. Accessed on February 17, 2024, from Historic New Acquisitions by Two Trailblazing Japanese American Painters | Smithsonian American Art Museum

Citation – Hibi, Hisako and Matsusaburo “George” Hibi papers, circa 1906-2022. “Art Exhibition Topaz Art School June 14th and 19th 1945. Photo of paper document. Accessed on February 17, 2024, from A Finding Aid to the Hisako Hibi and Matsusaburo “George” Hibi papers, circa 1906-2022 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (si.edu)

Citation – Nate D. Sanders Auctions. Lot#261 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster. Accessed on February 17, 2024, from Lot Detail – 1942 WWII Japanese Evacuation Poster — For Japanese Residents of San Francisco (natedsanders.com)

Citation – Ukai, Nancy. “Ibuki’s Doll, Silent Witness.” n.d. Funded in part by a grant from the U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Japanese American Confinement Sites Program. Accessed on February 17, 2024, from Ibuki’s Doll – 50 Objects

Citations

1 Portrait of Hisako Hibi, Photograph, 1985, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 38, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

2 Hisako Hibi, “Apricot Trees along Jackson Street,” Oil on Canvas, circa 1940, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 42, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

3 Hisako Hibi, “Spring #2, Hayward”, Oil on Canvas, 1949, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 42, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

4 Dorothea Lange, “Hisako and Ibuki Hibi with doll awaiting the bus to Tanforan,” Photograph, May 9, 1942, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 13, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.

5 Painting of Hayward Farmer – Hisako Hibi, Oil on Canvas, circa 1940, Hayward Area Historical Society.

6 Map, “State of California, Northern California coast, San Francisco to Fort Bragg prohibited or restricted zones,” 29th Engineer Reproduction Plant, 1943. San Jose State University Department of Special Collections and Archives

7 Hisako Hibi, “Four Seasons,” Oil on Canvas, 1983, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, In Peaceful Painter: Memoirs of an Issei Woman Artist, by Ibuki Hibi Lee, Page 63, Berkeley, CA: Heyday Books, 2004.