Intimidating Shoreline

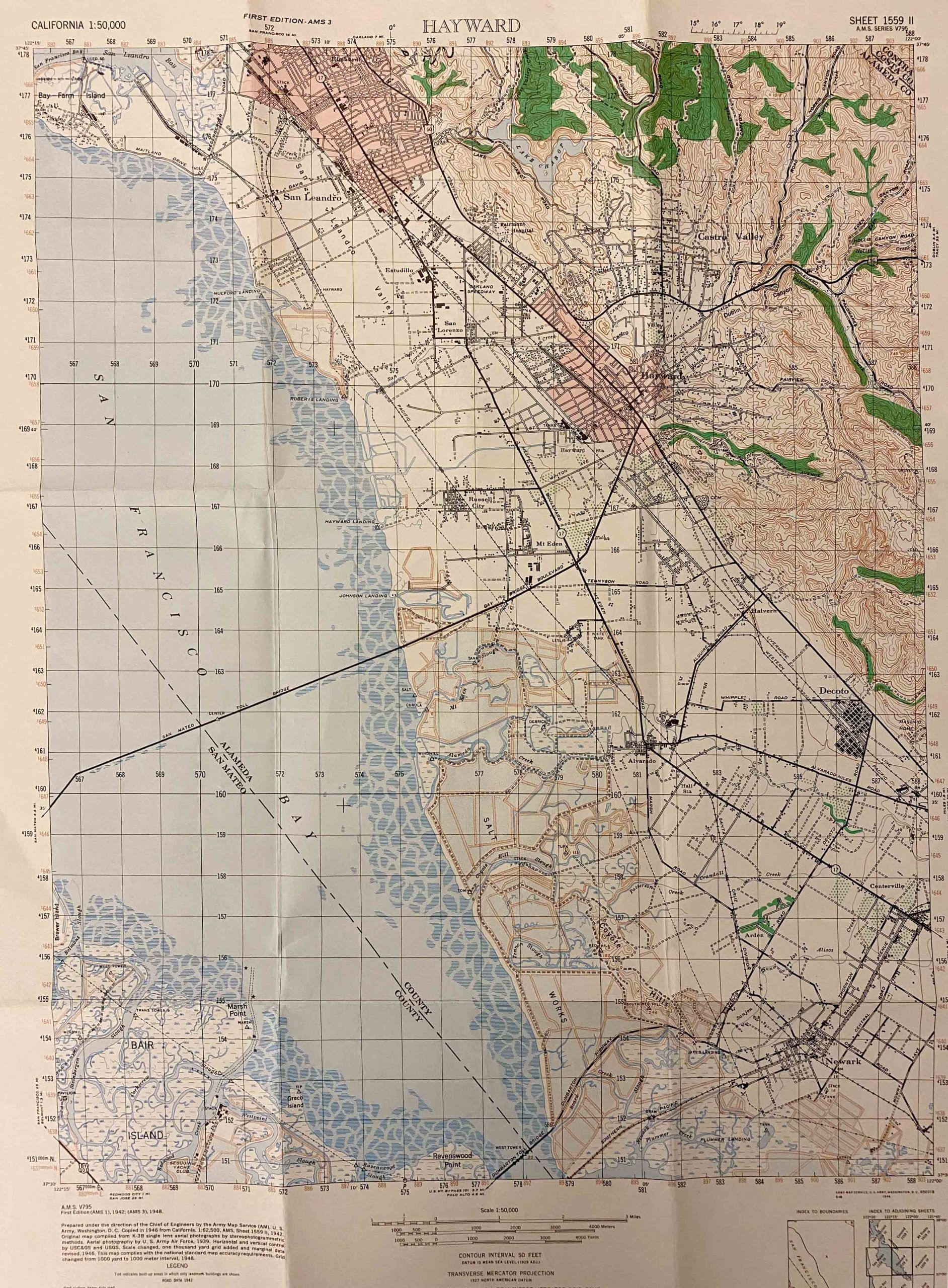

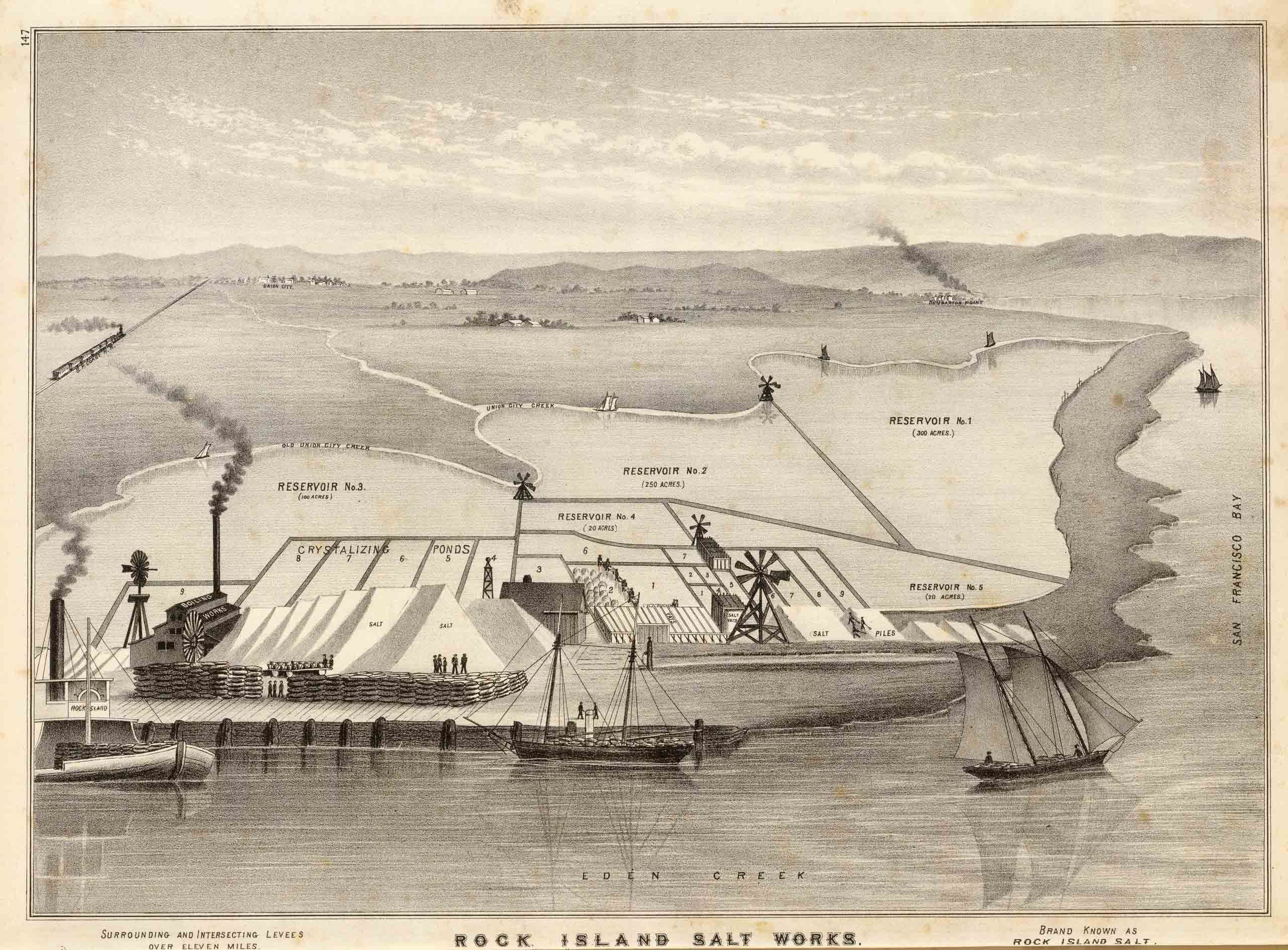

For nearly fifty years between the 1930s and 1980s, Hayward’s eight-mile stretch of San Francisco Bay shoreline was closed to the public by law. The shoreline was also intimidating, if not repellent, to human visitors: “White mountains of salt that hurts one’s eyes to look at in the sunlight” dominated the shoreline view from Hayward, while levees kept surreal evaporation ponds in “bright green,” “flamingo pink,” and “muddy yellow” hues separated from bay waters.1 Stretching across 8,000 diked acres, this colorful solar salt production stifled the bay’s tidal rhythms for decades, all but destroying historic marshes.

Industrialized Shoreline

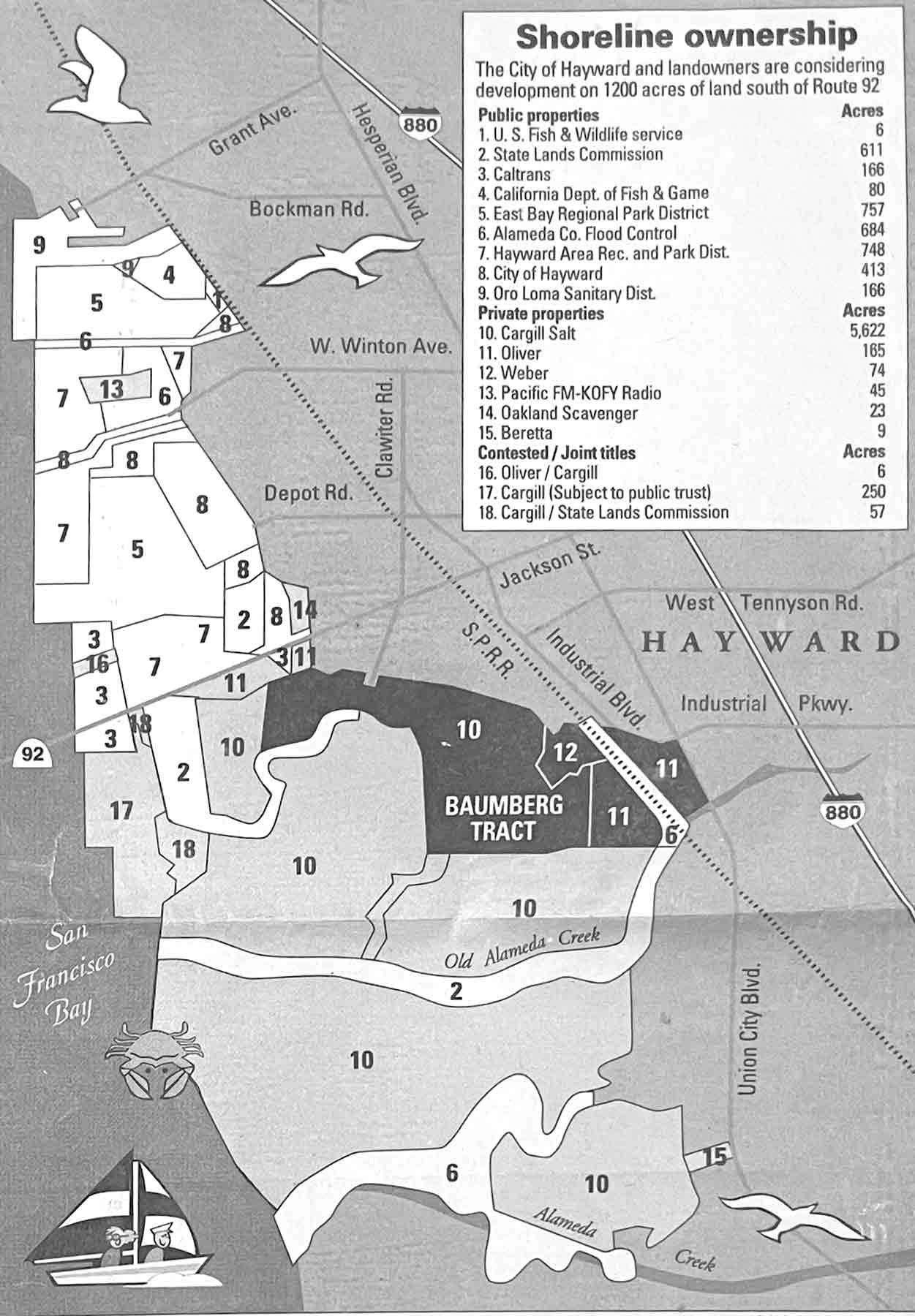

From the time of the Gold Rush, salt producers “converted mile after mile of dynamic tidal wetlands—salt marsh, mudflat, bay shallows—into stagnant pools” to meet booming household, agricultural, and industrial demands for salt.2 To support Hayward’s urban development in the twentieth century, remaining local shoreline acreage was taken up by landfills, sewage sanitation facilities, and rain runoff channels.

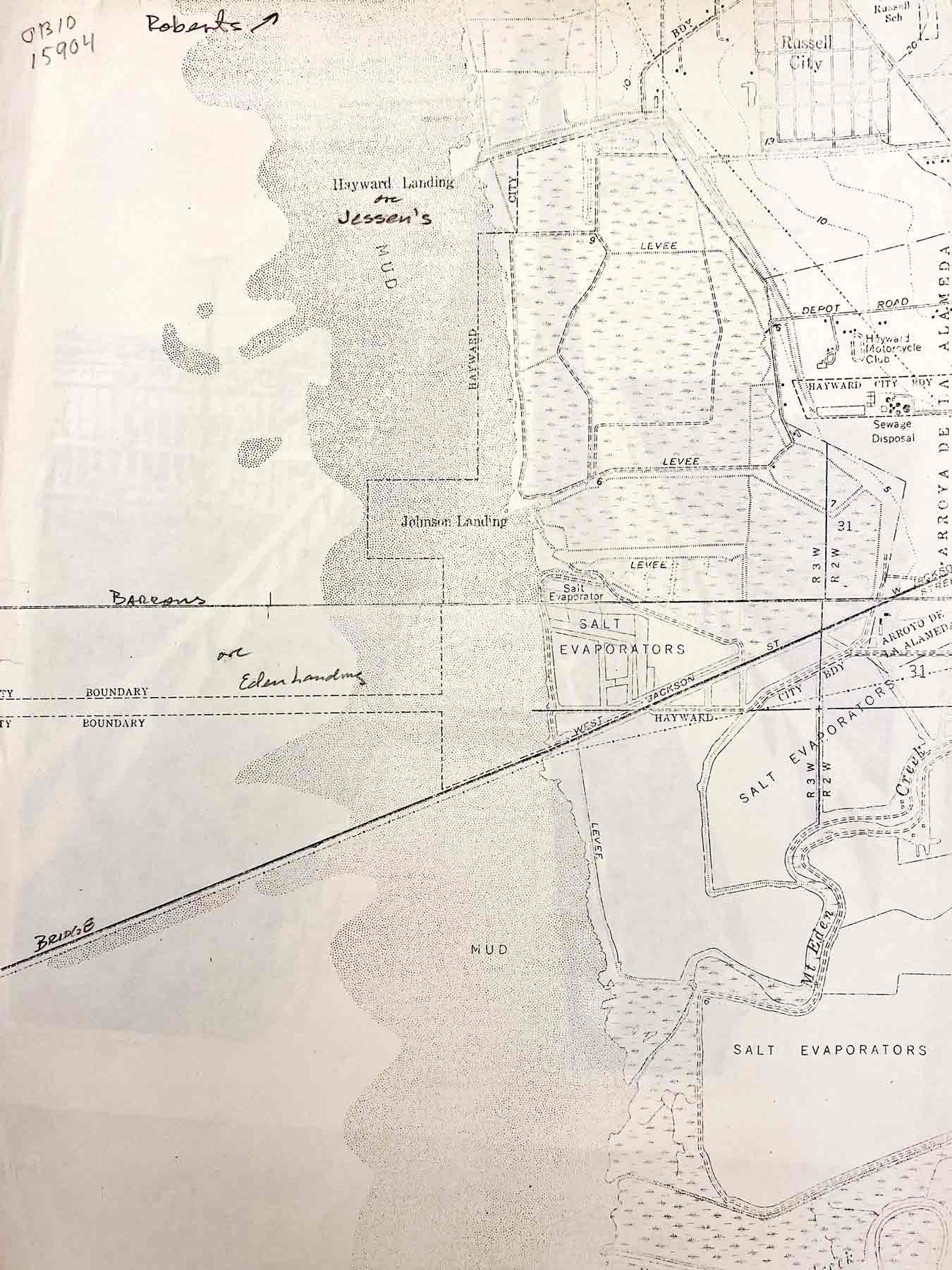

By 1976, Haywardians lamented that “private interests exert control over all of this Shoreline area” and warned off the public with a daunting terrain of salt evaporators, levees, dry diked zones, railroads, chain link fences, and tar pits. Between 1906 and 1963, the Trojan Powder Factory discharged explosives and released acids into the ground at Roberts Landing, at the northernmost end of the Hayward Shoreline.3

Students of the Shoreline

Local Haywardians trying to learn about the shoreline were undeterred by these hazards. They resorted to extraordinary measures—including illegal trespassing on private lands—to see the shoreline firsthand. At considerable personal risk, local Hayward science teacher Phil Gordon photographed little-seen shoreline wildlife and habitats. “I’ve been chased off the edge of the bay so many times,” Gordon confessed to a reporter in 1976.4

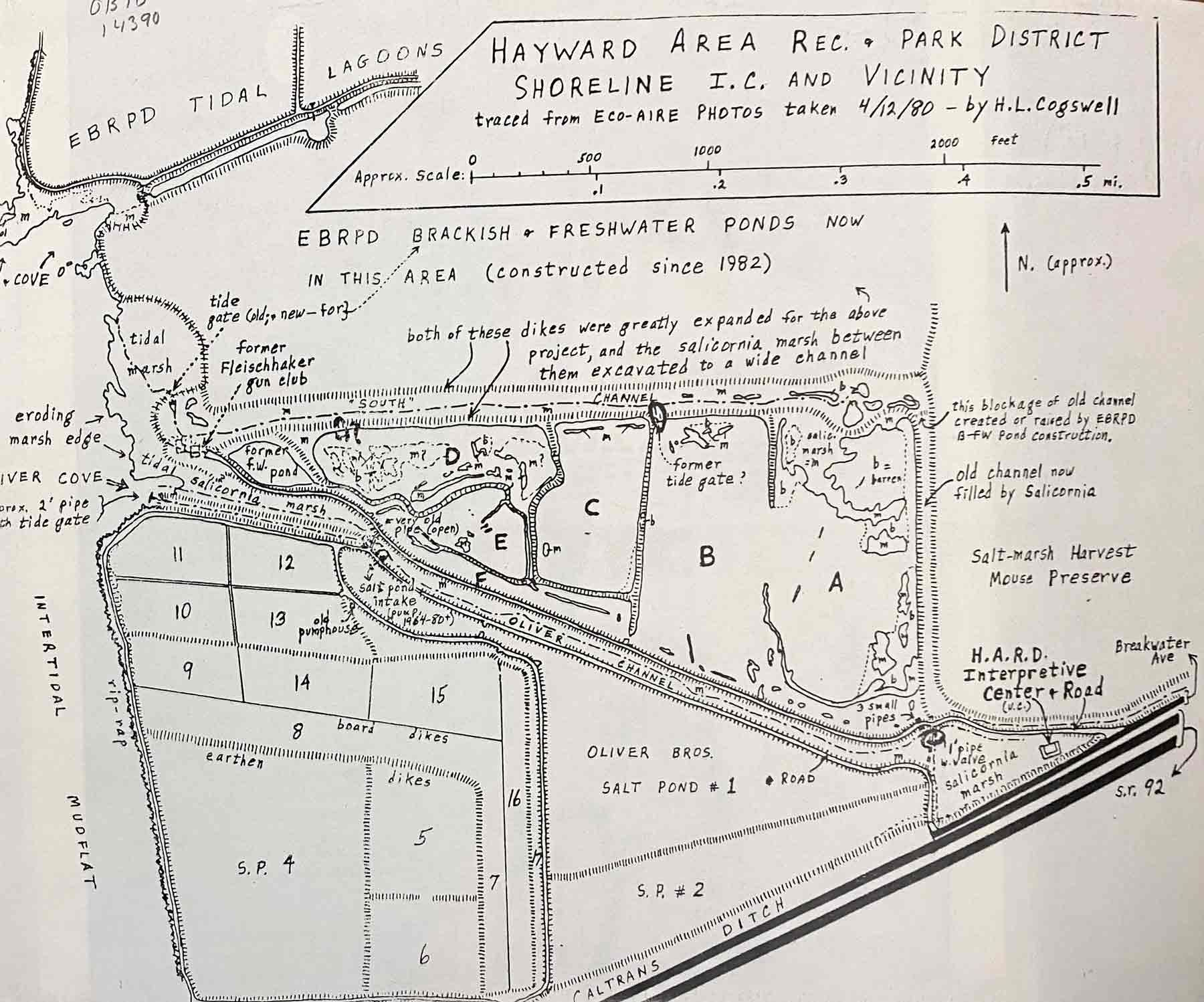

Hayward resident Howard Cogswell, a biology professor at California State University, East Bay (then Cal State Hayward), learned to fly small aircraft after finding hired pilots were resistant to the circling and low-dives demanded by wildlife observation.5 With aerial photos, Cogswell could precisely map the “edge” ecology of the Hayward Shoreline contending for survival with salt producers’ dikes, ponds, and ditches.6

Gordon and Cogswell both brought expertise as trained biologists to their vigilante studies of the Hayward Shoreline. Some students of the shoreline believed that “expertise” was not as significant as first-hand observation. Janice Delfino, a prominent citizen activist, described herself as “[having] an abiding interest in preserving and protecting the wetlands around [the] San Francisco Bay Area.”7 A retired nurse, she did not count on others to do the hard work of shoreline study. She and her husband, Frank Delfino, “would walk the area and look at things and try to decide what went on.”8 Precise evidence mattered: “We acquire maps, aerial photos, take our own photos, and gather other pertinent information on the wetlands we are striving to protect.”9

Given the shoreline’s ecological complexity and competing property rights and boundaries, work ensuring its protection was, and remains, unending. Even well-intentioned experts might propose dredging a creek to eliminate native pickleweed—essential to the survival of the salt marsh harvest mouse—in the name of beautification, or planting trees for a more park-like appearance—inviting non-native predators harmful to nesting shoreline birds.10 For over three decades, Janice Delfino attended meeting after meeting to ensure her hard-won knowledge helped inform decisions being made by the many public and private interests shaping the Hayward Shoreline’s future.

Citizen Advisors

In 1970, several local government bodies—including the City of Hayward, East Bay Regional Park District, and Hayward Area Recreation and Park District—created the Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Agency, or HASPA. Three years later, HASPA added a “Citizens Advisory Committee,” which included Phil Gordon and Janice Delfino.12 Cogswell was also involved in HASPA, representing the East Bay Regional Park District.

The work of these “citizen advisors” proved influential in HASPA. Gordon’s wildlife photos guided understanding of the ecology of the Hayward Shoreline, while Cogswell’s studies deepened knowledge of the more than seventy species of resident waterfowl and migratory birds found at the Hayward Shoreline. Cogswell’s wildlife counts helped decision-makers and the public understand that the Hayward Shoreline was one of the most significant and unique North American habitats for birds. Cogswell also drew attention to the multiple, complex “edge” ecologies at the Shoreline, where the “interplay of one system and another” creates “the greatest variety of life.”13

Delfino was seemingly everywhere all at once at public meetings and in courtrooms, stopping misguided landscapers and would-be amusement park and racetrack developers from wreaking havoc on a delicate ecology. She even took a deathbed confession from a guilt-ridden former industrial employee at the Shoreline about toxic releases into hidden water wells. “It took a lot of effort” to understand why “nothing was growing” in areas of the Shoreline, Delfino explained.14 The dying 92-year-old confessed his company’s environmental sins at the Shoreline to the Delfinos.15

Accomplishments

Howard Cogswell

Home to Various Endangered Species

Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse Habitat

We have a responsibility to restore and preserve the Hayward Shoreline, as it is home to a diverse array of wildlife who cannot survive without it. The environment of the Hayward Shoreline is extremely unique and already species are becoming endangered due to the destruction of similar ecosystems. The salt marsh harvest mouse, for example, is endangered, with “less than 10 percent of its historic habitat acreage [remaining],” lost due to human development.19 The least that we can do is help to protect the little land that is left for these species to call home.

Citations

2 Matthew Morse Booker, “From Real Estate to Refuge,” in Down by the Bay, 1st ed., San Francisco’s History between the Tides (University of California Press, 2013), 162, https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt2jcbxr.10.

3 Janice Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” in The Baumberg Tract: From the Proposed Shorelands Development to the Wetlands Restoration (Eden Landing Ecological Reserve), 1982-1999, California Water Resources Oral History Series (Berkeley, CA: Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000), 342–44, http://archive.org/details/baumbergtract00challrich.

4 Steve Fisher, “The Scientists in Their Hipboots,” The Argus, February 8, 1976, sec. Brightside.

5 Howard L. Cogswell, “College Professor, Ornithologist, Active Citizen,” in The Baumberg Tract: From the Proposed Shorelands Development to the Wetlands Restoration (Eden Landing Ecological Reserve), 1982-1999, California Water Resources Oral History Series (Berkeley, CA: Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley, 2000), 48–49, http://archive.org/details/baumbergtract00challrich.

6 Fisher, “The Scientists in Their Hipboots.”

7 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” 316.

8 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” 334.

9 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” 316.

10 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” 333–36.

11 Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Agency, Hayward Area Shoreline Planning Program: A Shared Vision (Hayward, CA, 1993), 1.

12 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment.”

13 Fisher, “The Scientists in Their Hipboots.”

14 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment,” 343.

15 Delfino, “Activist for the Environment.”

16 Hayward Area Recreation and Park District, “Hayward Shoreline Interpretive Center (HSIC),” Hayward Area Recreation and Park District, n.d., https://haywardrec.org/1991/Nature-Centers.

17 US Fish and Wildlife Service, “Focal Listed Species: Salt Marsh Harvest Mouse,” in Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California (Sacramento, CA, 2013), 133, https://www.fws.gov/project/california-tidal-marsh-ecosystem-recovery.

18 “Hayward Regional Shoreline: Restore Hayward Marsh Project” (East Bay Regional Park District, October 30, 2020), https://www.ebparks.org/sites/default/files/hayward_marsh_brochure_10-30-2020_update.pdf.

19 US Fish and Wildlife Service, Recovery Plan for Tidal Marsh Ecosystems of Northern and Central California (Sacramento, CA, 2013), viii, https://www.fws.gov/project/california-tidal-marsh-ecosystem-recovery.