Introduction

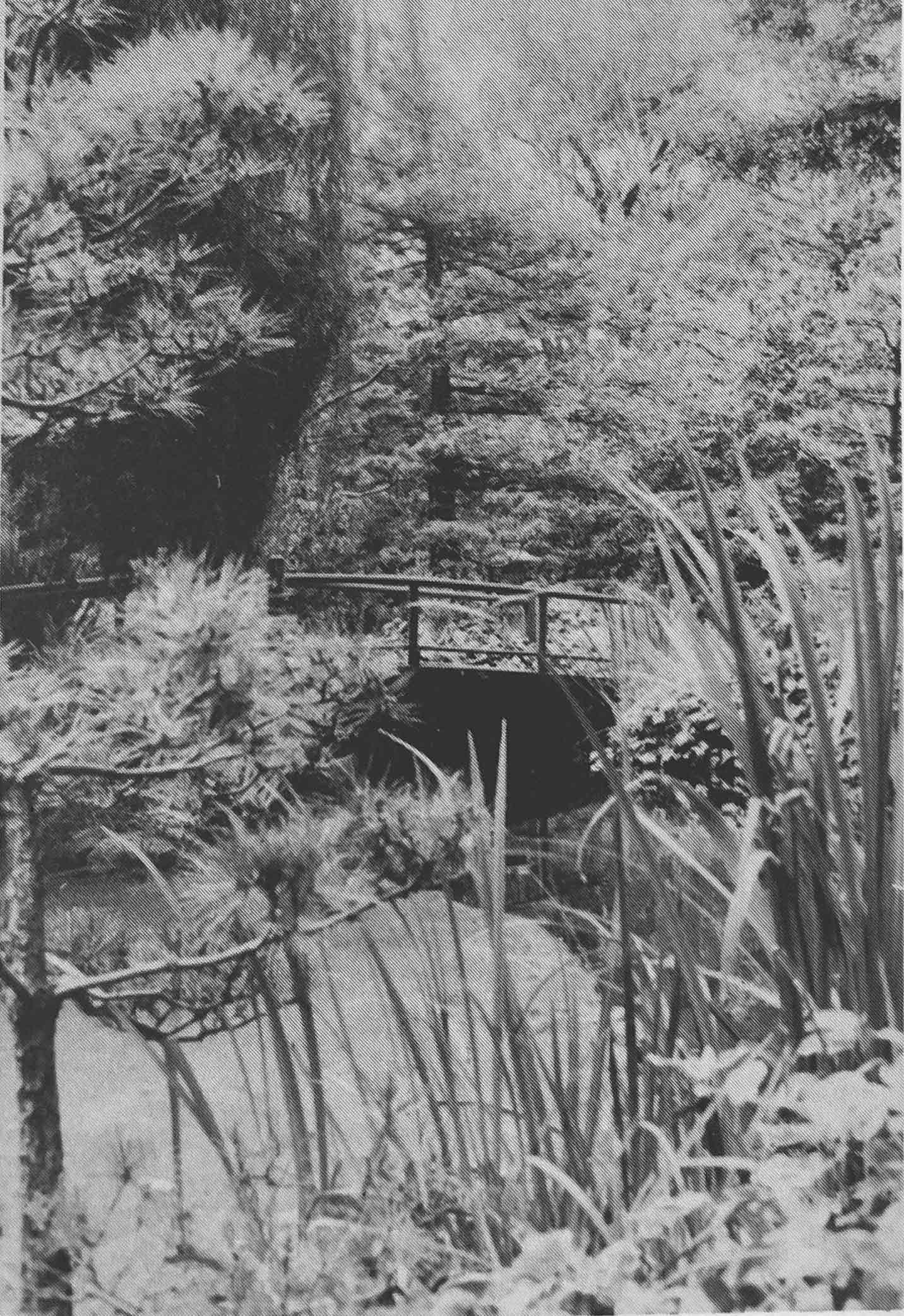

The Japanese Garden at Mt. Eden preserves an extraordinary history within Hayward. Created by the Shibata family, It was constructed upon the grounds of their successful Mt. Eden Nursery. Built and tended to for over seventy years, the Japanese Garden at Mt. Eden still exists amid nondescript commercial buildings.

The leading landscape architect, Koyuri Shibata, who descended from a long line of Japanese Buddhist ministers, incorporated her religious expertise and ongoing studies to shape the Japanese Garden’s design and structural features while symbolizing meaning. It came to life with the assistance of the surrounding community. The Shibata family was aided by hired laborers and community members who planted trees and plants and delivered over 1,000 tons of rock and stone from a local quarry.

The decades-long construction required creative problem solving, complex logistical planning, unyielding passion, and artisanship. At the Japanese Garden, “garden sessions,” which included storytelling and singing, drew crowds of Haywardians through the 1920s and 30s.

The Japanese Garden represents a family, a community, a religious belief, and a unique Hayward home. This section provides context for understanding the origins and development of the Japanese Garden at Mt. Eden between the 1920s and 1940s.

Shibata Family Tree

The Shibata Family’s arrival and first years in America

“In those days in Japan, family businesses were passed down to the oldest son, the chonan. Since father was the younger of two sons and had limited schooling, he had no place to go. But he had heard about America and all its promised opportunities.”

Yoshimi Shibata – Across Two Worlds Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower pg. 4

Zenjuro, the patriarch of the Shibata family, crossed the Pacific and arrived in San Fransico in 1902. To survive in the Bay Area, he worked grueling manual labor jobs, including employment with the railroad and harvesting crops.

Zenjuro discovered that he could earn greater profits by growing and selling flowers. After saving his earnings, he purchased a three-acre parcel of land on 105th Avenue in Oakland. After three years, he was financially stable enough to marry and accepted a marriage proposal with Koyuri Otsuka. He traveled back to Japan, and they were married in Itoshima Fukuoka on October 11, 1913. The newlyweds made Oakland their home and began to expand their family while managing a successful floral business. They had two of their six children, Yoshio and Yoshimi, before their move to Hayward.

The Beginning of the Nursery

“Being Japanese, Father couldn’t buy good land, but one day a marshy plot of land caught his eye. It was not suited for farming at all—the land flooded on one end and it was near the railroad tracks. But my father saw the flood and said, “Well that’s good. I’ll put a water pump on that end to water the greenhouse.” So he looked at that flooded piece of land as an asset.”

– Yoshimi Shibata ~ Across Two Worlds Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower pg. 10

As floral demand grew, the Shibata family was required to reassess their operations. Oakland, which had become increasingly populated, no longer met their needs. Zenjuro searched for a city that would enable his family to thrive and their business to expand. He found that in Hayward. Here, he discovered a twenty-six-acre plot of land in rural Mt. Eden Township. It was a marshy plot that flooded frequently; however, Zenjuro saw potential and was determined to purchase it. Due to the Alien Land Law, which prevented non-citizens from owning land, Zenjuro, with a large loan from the Bank of Italy, arranged to purchase it in his eldest son Yoshio’s name. In 1918, Zenjuro, Koyuri, and two of their future six children moved to Mt. Eden Township. This land would become Mt. Eden Nursery, the Japanese Garden, and their new home.

The community created by the Nursery

“Father and his workers both lived in a society that was unfamiliar and often hostile. So our nursery became a society of common people from different heritages. It was a good community, and Father found out that many of his life’s experiences were common to the other immigrants.”

– Yoshimi Shibata ~ Across Two Worlds Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower pg. 17

Of the land Zenjuro purchased, not all was dedicated to the operation of the Mt. Eden Nursery. Immigrants of Japanese and later Mexican and Portuguese descent were hired as laborers to address the increasing demands. To accommodate their needs, Zenjuro built facilities and a labor camp with numerous barracks to house the laborers and their families. His son Yoshimi mentions in his memoir how the camp became a community. Here, those of Japanese heritage lived surrounded by their culture, language, and fellow Japanese in the middle of California. The Mexican and Portuguese camp occupants created their own community space but found common ground with the Shibata family and the other laborers. All had suffered similar hardships related to relocating to and living in an unfamiliar country. Despite the language barrier, the diverse population at Mt. Eden Nursery worked and lived harmoniously. The Nursery continued to change and grow and became home to many foreigners.

Early in the Japanese Garden’s history, continuous flooding formed a natural pond on the property. Later, it was converted into a reservoir to store water. Zenjuro considered using it to breed goldfish for additional revenue, but Koyuri thought of a different plan. She began to shape the reservoir into a water feature and convert the surrounding area into the Japanese Garden. The Shibata family split their time and resources between the nursery and the garden. During this time, Koyuri was diagnosed with cancer and underwent successful surgery. The doctors warned that her cancer would likely return. With the looming possibility of death, Koyuri used the Japanese Garden as a place to forget about illness. In his memoir, Yoshimi refers to it as his mother’s garden and how it became a family project as they worked to create a place of enjoyment for themselves and their friends. By bringing Koyuri’s dream to fruition, the Shibata family infused their Japanese heritage with their home and Hayward.

WWII and Leaving Mt. Eden

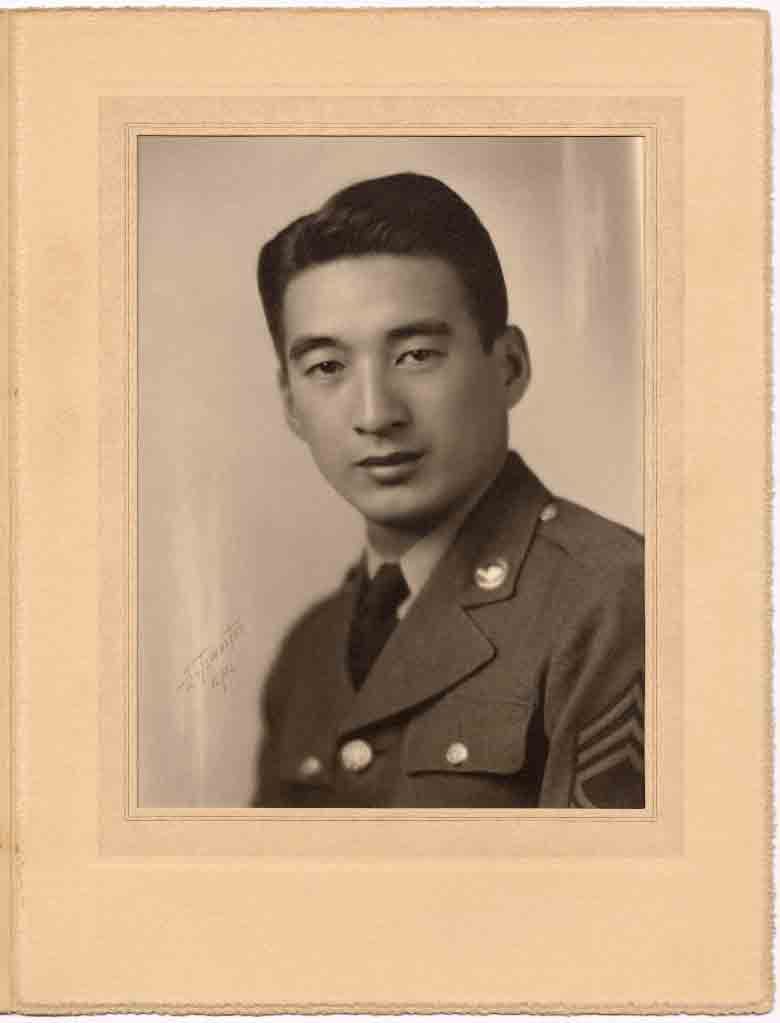

Immediately following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the Shibata family, including Yoshito, who was serving in the U.S. military, were confined to their residences and made to hand over government-deemed “contraband,” including weapons, cooking knives, lanterns, and flashlights. The family was allowed to retain a few cooking knives and one flashlight. Yoshimi discusses in his memoir how he argued with the Sheriff, proclaiming that he was an American. However, due to racist and wartime fears and changes in government policy, all Japanese Americans were seen as only Japanese and a risk to America. The family did try to help with the U.S. war efforts but were treated with distrust and persecution.

The restrictions on Japanese Americans included travel limitations of at most 5 miles from their residence. This restriction caused issues for the Shibata family’s nursery as they needed to travel to sell their flowers. Additionally, the stores in the Bay Area where the Shibata’s sold their flowers were changing to support the military effort. The Shibata family and their fellow flower growers attempted to ship their flowers to the Southern California Flower Market, but after a few weeks, the market was closed down.

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal and migration of individuals of Japanese descent. Panic quickly spread within Japanese communities and the flower growers’ organizations. Yoshimi tried to find someone to care for the nursery before the family’s relocation, but no one wanted to involve themselves with the Japanese.

The family eventually left Mt. Eden Nursery to their long-term customer, William Zappettini, an Italian immigrant, who ran the wholesale store through which they sold their flowers. He continually cared for the nursery until their return in 1945.

Jerry continued to serve and later became part of the U.S. Military Intelligence. When able, he checked on Mt. Eden Nursery, Mr. Zappettini, and communicated with his family on the condition of their home while they were incarcerated and he was in California.

WWII and Leaving Mt. Eden

Immediately following the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor, the Shibata family, including Yoshito, who was serving in the U.S. military, were confined to their residences and made to hand over government-deemed “contraband,” including weapons, cooking knives, lanterns, and flashlights. The family was allowed to retain a few cooking knives and one flashlight. Yoshimi discusses in his memoir how he argued with the Sheriff, proclaiming that he was an American. However, due to racist and wartime fears and changes in government policy, all Japanese Americans were seen as only Japanese and a risk to America. The family did try to help with the U.S. war efforts but were treated with distrust and persecution.

The restrictions on Japanese Americans included travel limitations of at most 5 miles from their residence. This restriction caused issues for the Shibata family’s nursery as they needed to travel to sell their flowers. Additionally, the stores in the Bay Area where the Shibata’s sold their flowers were changing to support the military effort. The Shibata family and their fellow flower growers attempted to ship their flowers to the Southern California Flower Market, but after a few weeks, the market was closed down.

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, which authorized the forced removal and migration of individuals of Japanese descent. Panic quickly spread within Japanese communities and the flower growers’ organizations. Yoshimi tried to find someone to care for the nursery before the family’s relocation, but no one wanted to involve themselves with the Japanese.

The family eventually left Mt. Eden Nursery to their long-term customer, William Zappettini, an Italian immigrant, who ran the wholesale store through which they sold their flowers. He continually cared for the nursery until their return in 1945.

Jerry continued to serve and later became part of the U.S. Military Intelligence. When able, he checked on Mt. Eden Nursery, Mr. Zappettini, and communicated with his family on the condition of their home while they were incarcerated and he was in California.

Tule Lake, Chicago, and the Rebuilding of Mt. Eden

During the war, the Shibata family spent a portion of their time at the Tule Lake Relocation Center on the California-Oregan border in Newell, California. It wasn’t until 1945 that the Shibata family returned to Mt. Eden.

Their time in the camp was hard, especially with emotions running high over the actions of the American government. Each of the Shibata family men worked within the camp doing various jobs. Yoshimi held positions of higher importance, such as co-op manager of a company established by a few stores running within the camp. After eleven months in the Tule Lake camp, Yoshimi was released for good behavior and went to work at the Premier Rose Garden, a greenhouse company near Chicago, Illinois.

After he was settled, his family joined him in Chicago. They remained in Illinois until California reopened its borders to the Japanese. Yoshimi was able to obtain a special permit to go and check on the nursery in December 1944. When he returned, he observed that the nursery and garden had been poorly cared for. Compounding the situation, Zappettini’s laborers threatened Yoshimi out of fear of losing their jobs and disliked working for a Japanese man. When Yoshimi returned to Chicago, he hired Nisei workers as security to help him take back the nursery. He returned and sorted out the situation to the best of his ability before his parents arrived from Chicago. Shortly after his parents returned to Mt. Eden, he was drafted into the Army like his brothers. Yoshimi petitioned for military release, but it was denied. With all of the Shibata sons now deployed, his parents and younger sister cared solely for the nursery and garden.

World War II ended in 1945, enabling Yoshimi and his brothers to return home. Operating the nursery without the entire family and laborers had been challenging. With the return of Yoshimi and his brothers came family friends who had lost their homes and businesses and were searching for a new start. Together, they rebuilt the nursery greenhouses, garden, and remodeled the tea house into a place where the family could live. Eventually, Mt. Eden Nursery was back on its feet after years of hard work. With his brothers’ support, Yoshimi continued to grow the business and shape the flower market in California.

Tule Lake, Chicago, and the Rebuilding of Mt. Eden

During the war, the Shibata family spent a portion of their time at the Tule Lake Relocation Center on the California-Oregan border in Newell, California. It wasn’t until 1945 that the Shibata family returned to Mt. Eden.

Their time in the camp was hard, especially with emotions running high over the actions of the American government. Each of the Shibata family men worked within the camp doing various jobs. Yoshimi held positions of higher importance, such as co-op manager of a company established by a few stores running within the camp. After eleven months in the Tule Lake camp, Yoshimi was released for good behavior and went to work at the Premier Rose Garden, a greenhouse company near Chicago, Illinois.

After he was settled, his family joined him in Chicago. They remained in Illinois until California reopened its borders to the Japanese. Yoshimi was able to obtain a special permit to go and check on the nursery in December 1944. When he returned, he observed that the nursery and garden had been poorly cared for. Compounding the situation, Zappettini’s laborers threatened Yoshimi out of fear of losing their jobs and disliked working for a Japanese man. When Yoshimi returned to Chicago, he hired Nisei workers as security to help him take back the nursery. He returned and sorted out the situation to the best of his ability before his parents arrived from Chicago. Shortly after his parents returned to Mt. Eden, he was drafted into the Army like his brothers. Yoshimi petitioned for military release, but it was denied. With all of the Shibata sons now deployed, his parents and younger sister cared solely for the nursery and garden.

World War II ended in 1945, enabling Yoshimi and his brothers to return home. Operating the nursery without the entire family and laborers had been challenging. With the return of Yoshimi and his brothers came family friends who had lost their homes and businesses and were searching for a new start. Together, they rebuilt the nursery greenhouses, garden, and remodeled the tea house into a place where the family could live. Eventually, Mt. Eden Nursery was back on its feet after years of hard work. With his brothers’ support, Yoshimi continued to grow the business and shape the flower market in California.

The Expansion of the Flower Business

“By early 1947, my father was deathly ill. As he was dying, he called me to his bed and said, “You are the chonan, the oldest son. I will need you to fill my shoes.” He also asked me to keep up the garden to continue fulfilling my mother’s dreams.”

– Yoshimi Shibata ~ Across Two Worlds Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower pg.85

Before WWII, Zanjuro had begun to pass the reins of the family business to his son Yoshimi. Following Zenjuros’s death in May 1947, Yoshimi began to plan the company’s national expansion with his brothers’ support. The family worked hard as they began navigating the post-World War II economy. The family business began evolving as the brothers focused on interests outside the nursery. Yoshimi began to sell their flowers to the East Coast through a retired Army C-46 cargo plane, which he hired a pilot to buy and fly for him.

A few months after his father’s death, Yoshimi met his future wife, Grace, through an old friend of his parents. They married in September of 1947, and Grace began to help Yoshimi with the bookkeeping, administration, and business relations aspects of the flower business. Grace’s role enabled Yoshimi to focus on the nursery and care for the family.

Drawing from his time at Tule Lake, he started to create co-op groups of flower growers to help develop the flower market nationally for California flower growers. Due to the limited supply of cultivation land in the Bay Area and the effects of air pollution on their greenhouses, Yoshimi created greenhouse companies in Salinas, Monterey, and Carmel. The Shibata’s business expansion was successful for a time; however, with demand shifting from California to international floral suppliers, Yoshimi increasingly lost customers. This loss of revenue led to hard times for the Shibata family. Again, changes in the market would force the Shibata family business to adapt, including the family’s decision to leave Mt. Eden as their home base of operations.

MT. EDEN NURSERY DISMANTLED & THE GARDEN PRESERVED

“A garden is like a human being; it will respond to whatever interest you put into it. It grows and matures as time goes on. There are all types of Japanese gardens, some religious and others more horticulturally based. I grew up being garden-minded and I incorporated some of the ideas from my parents into my own yard. Today as I walk through the Mt. Eden/Hayward Tea Garden, I cannot help but think of my parents and some of the things they believed in.”

– Yoshimi Shibata ~ Across Two Worlds Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower pg.161

With the change in the floral market, the Shibata family business had to adapt. The market was no longer just about growing beautiful flowers as people became consumed with the price. In 1994, as Hayward expanded, the greenhouses aged, and the need for them ended. The Shibata family decided that the family’s original home, packing house, and greenhouses would be torn down. After 76 years, the Shibata family and its business had outgrown Mt. Eden Nursery. Afterward, the brothers divided the business assets and continued their lives away from Hayward. Over the next four years, the land was sold off, and the remaining portion was leased to a developer. Throughout this process, the Shibata family preserved the Japanese Garden and teahouse.

Today, the Japanese Garden remains accessible to the public. To find it, one must look within the densely constructed commercial and residential structures that have transformed the once-fertile fields. The Japanese Garden continues to embody the history of the area and the Shibata family. Like the Shibata family, the garden is a fusion of Japanese and American heritage. Here in Hayward, they built a home, business, and a place to express their culture and share it with the surrounding community.

Citations

1 Jouko van der Kruijssen, Images of the Shibata Family Garden, Photographs, 2022.

2 “Shibata family”, Photograph, 1930, In Across Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower, by Yoshimi Shibata, Page 9, Pasadena, CA: Midori Books, 2006.

3 Chas. E. Mace, Photograph of [Jinjiro Shibata, Yoshimi Shibata, Joe Kodama, and Seiji Sato at The Mount Eden Nursery and Greenhouses], June 1945, Mt. Eden, CA,War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Collection, Online Archives of California, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA.

4 “Portrait of Yoshito Shibata in military uniform”, Photograph, 1940-1950, Courtesy of Yuriko Domoto Tsukada Collection, Densho Digital Repository.

5 Mt. Eden Flower Company, “Yoshimi Shibata: Flower Industry Pioneer,” YouTube, September 21, 2015, 2:13

6 Mt. Eden Nursery, Photograph, 1940s, Hayward, Growing a Community: Pioneers of the Japanese American Floral Industry.

7 Mt. Eden’s Japanese Language School, circa 1934, The Story of Mt. Eden, Hayward Area Historical Society Digital Archives, Hayward, CA.

8 Mt. Eden Nursery Brochure, Photographs, Hayward Business & Industry: Flowers and Nurseries, Hayward Area Historical Society Archives, Hayward, CA.

9 Hikaru Iwasaki, Photograph of [Yoshimi Shibata], September 1944, Melrose Park, IL, War Relocation Authority Photographs of Japanese-American Evacuation and Resettlement Collection, Online Archives of California, Bancroft Library, Berkeley, CA.

10 “Image of barracks”, Photograph, circa 1940, In Across Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower, by Yoshimi Shibata, Page 65, Pasadena, CA: Midori Books, 2006.

11 “Evacuee train arrives at the Tule Lake Relocation Center”, Photograph, 1942, In Across Two Worlds: Memoirs of a Nisei Flower Grower, by Yoshimi Shibata, Page 64, Pasadena, CA: Midori Books, 2006.

12 Mt. Eden Flower Company, “Yoshimi Shibata: Flower Industry Pioneer,” YouTube, September 21, 2015, 4:10.

13 Yoshimi Shabita inside the nursery, Photograph, “About Us,” Mt. Eden Flower Co.

14 Yoshimi Shabita surrounded by flowers, Photograph,“About Us,” Mt. Eden Flower Co.